Through all stages of its existence, the genre of hip-hop and rap music has been a topic of discourse for many. While the common misconception that hip-hop is nothing but a promoter of gang violence and misogyny is a massively ignorant overgeneralization of the genre in the public eye that feels like an outdated thing of the past, the more subtle biases and prejudices towards rappers and the content they preach is still very much alive even today.

Hip-hop has found a way to overcome many of its most vocal critics, but our society has still seemed to find a way to further marginalize the means of personal and artistic expression from what is already one of the most socially marginalized groups in our country.

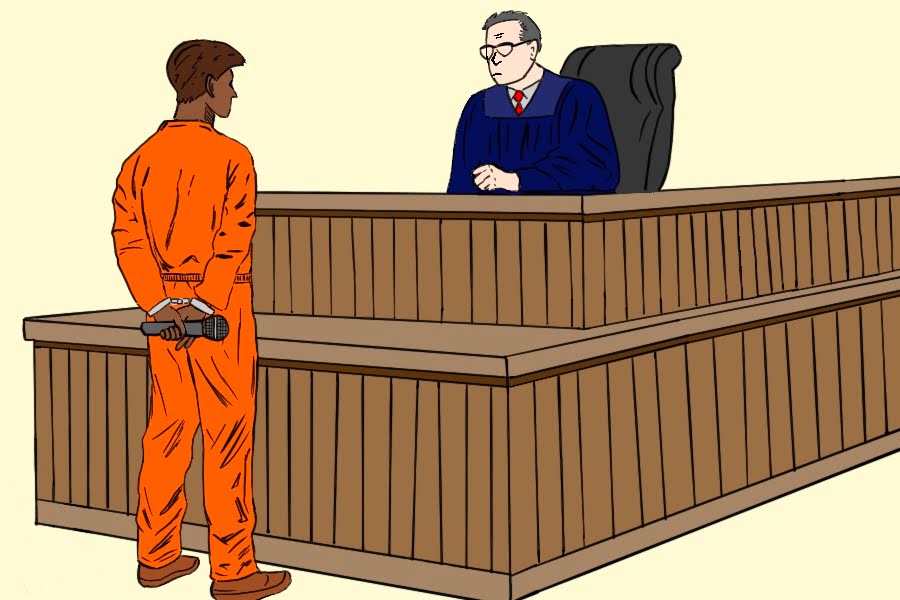

On Oct. 31, 2024, the criminal trial of Atlanta-based rapper Young Thug, whose real name is Jeffery Williams, effectively came to an end. Williams accepted a plea deal that sentenced him to 15 years of probation, with additional jail time possible in the case of a violation, closing a lengthy and strenuous legal odyssey for Williams that had been ongoing since his initial arrest on May 9, 2022.

Williams was one of 28 co-defendants charged in a massive 56 count RICO indictment alleging that his label, Young Stoner Life (YSL) Records, operated as a criminal organization. While the poorly conducted nature of the YSL trial is worthy of a breakdown in its entirety, the focus for many was Judge Ural D. Glanville’s ruling on Nov. 9, 2023 that song lyrics by the defendants would be allowed to be used as evidence in the proceedings.

Glanville asserted that this decision was not a violation of the defendant’s right to free speech; he claimed that the content of the lyrics presented were not a reason for prosecution, but rather a means to prove whether or not the defendants were guilty. However, the verdict faced stark opposition from Williams’s legal team and other advocates for the freedom of artistic expression, who claimed that the decision effectively denies rap music’s status as art.

The usage or attempted usage of rap lyrics as presentable criminal evidence is a phenomenon that has occurred many times before. Some states do have legislation in place in order to try and limit the ability of prosecutors to present artistic expression, such as rap lyrics, as credible evidence. However, most trials of this nature including the YSL case allow lyrics to be “conditionally” submittable, after analysis by a judge.

Another high profile instance of this in recent years is in the ongoing case of State of Florida v. Jamell Demons (stage name YNW Melly). Upon resuming proceedings in the wake of a mistrial, the prosecution moved to present a number of songs and musical content released by Demons as evidence, despite prosecutor Kristine Bradley previously asserting that they would not out of respect for the rights of artistic expression. The case of Demons is even more high stakes than Williams’s, as Demons faces charges of murder and a possible death sentence.

As a general rule, most state judicial systems will permit rap lyrics as credible evidence under the specific condition that the lyrics directly relate and possibly prove the exact actions which the defendant is under trial for. Their intention can not be to try and play to a negative bias a jury may already have or conceive in regards to the defendant’s character.

On face value, these conditions may not seem particularly unreasonable or unfair. If these rappers knowingly released music that in some way incriminates them, what is stopping those apparent confessions or admissions of guilt from being scrutinized in court? However, when looking deeper at the broader implications of normalizing the use of rap lyrics as criminal evidence, what society is faced with is a serious threat to the freedoms of artistic and personal expression. This is especially so in light of historical and cultural context and the prevalent socio-economic and racial undertones, all factors that are essential to understanding these lyrics’ relevance as art, not evidence.

From the very origins of hip-hop as a genre and cultural movement in The Bronx in the early 70s, one of the main components of the art form in its purest and most traditional sense has been to serve as a call to action, seeking to speak out against the rampant socio-economic hardships inflicted upon lower class Caribbean and African-American citizens at the time. Years later, when west coast rap group NWA burst onto the scene with their 1988 album “Straight Outta Compton,” it brought the gritty and unapologetic hip-hop subgenre of gangsta rap to the forefront of the mainstream, and all of its violent and confrontational imagery with it.

While the record, and many future gangsta rap projects to come, became wildly successful and popular, the music also fell under heavy scrutiny from critics and consumers alike. They claimed that the genre dangerously glorified gang violence, substance use and misogyny, in the process of this criticism ignorantly overlooking the art form’s value as an expression of the desperate conditions these rappers and their communities went through on a day to day basis.

Soon, the higher-ups in the music industry began to see that hip-hop presented a new, appealing and marketable aesthetic that could be capitalized on for profit. Listeners were drawn in by the newfound opportunity to consume and embody a persona of perceived toughness or coolness that had previously been attainable from a genre like rock n’ roll, only now packaged differently.

Hip-hop had begun as a way to give a voice to the disenfranchised, and now, whether through selfishly driven capitalistic incentives or not, that voice was being heard and encouraged by a large part of American society. For that reason, much of the popular rap music that circulated at the time, despite often being performed by artists with little to no ties to the lifestyle they claimed to lead, was an often very similar entity content and style-wise, as that was what the mainstream found most digestible and appealing, especially the largely white demographic they now had to appeal to in order to ensure staying power.

Even in today’s era the most successful rappers tend to come from the trap subgenre, a style of hip-hop hailing from Atlanta that has essentially replaced gangsta rap as the most commonly mainstream and best selling lane of rap music, with it’s similar lyrical content and more trendy and digestible sound in the current environment. Some of the most imitated and commercially successful rap artists of the past few years all make their music under a very clear trap aesthetic, such as Future, 21 Savage, Migos and, of course, Young Thug himself.

The YSL trial is just the most recent, high profile example of how allowing the introduction of rap lyrics into criminal court cases as evidence directly undermines all of this. Society is turning a form of self-expression and means of escape for a whole generation into grounds to essentially punish artists for their struggle. If this trend continues, rappers may become unjustly motivated to curb their full creative and artistic potential, just so that they aren’t risking their livelihoods. In an interview with NPR, Kevin Liles, the founder of hip-hop record label 300 Entertainment, puts things perfectly.

“Our creativity cannot be our confession. Our imagination can’t be our indictment,” Liles said.

What’s worse is that many Black artists adopting personas through their music in order to try and garner mainstream appeal are now being punished for trying to take advantage of one of the few means of socio-economic advancement readily allowed to them by the often privileged and white upper levels of our broader society. Liles calls out this hypocrisy.

“If you want to change what they talk about, change the conditions that they live in,” Liles said. “If you want to have thought leaders and not warriors, then give them the opportunity to use their mind, to use their creativity to actually do more.”

A textbook example of this is the case of Olutosin Oduwole, who was arrested in 2007 while a student at Southern Illinois University after the police found what they claimed was the threat of a shooting that he’d scribbled on a piece of paper found in his car. Charis Kubrin, a professor of criminology at the University of California, Irvine and co-author of the legal guide “Rap on Trial,” speaks on this case in her 2014 TEDx Talk. Having been asked to testify as an expert witness in Oduwole’s case, Kubrin recounts an important detail that she brought to the attention of the jury in her testimony.

“If you flipped the paper over, there were line after line of what appeared to be rap lyrics,” Kubrin said.

Further, the police found notebooks’ worth of lyrics in Oduwole’s trailer, all similar to the content one would hear in the songs of an aspiring gangsta rapper. With this in mind, Kubrin reasoned that the aforementioned threatening lines of text likely had been written to serve as the intro or outro for a song and provided this insight to the jury. In spite of all of this, the jury found Odulwole, a college student with no prior criminal record, guilty of attempting to make a terrorist threat. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

While the conviction was later overturned, the case represents the consequences of normalizing the use of rap lyrics in court–subjugating rappers to stereotypes and biases surrounding their music, which are held by much of the general public, and by extent, jurors. Again, certain states, such as California, have passed legislation to try and make prosecutors provide more valid reasons to submit lyrics as evidence that relates directly to the charges at hand. However, as pointed out by Awais Arshad, Priya Chaudhry and Jeffrey Movit in their guest column on the topic for Billboard.com, there are loopholes to these laws.

“While the actual and proposed California, New York and federal statutes would make it harder for prosecutors to use rap lyrics as evidence of a crime, they do nothing to prevent prosecutors from alleging that rap lyrics themselves are an element of a crime—specifically, the so-called “overt act” element of a conspiracy crime,” the column reads.

Conceptually, it is unquestionably insane to think that art in any way, shape or form could be seen and used in court under the guise of evidence. Art, by definition, blurs the line between fact and fiction. It is also not necessarily autobiographical, especially in the case of lyrics. Except, of course, when it comes to hip-hop, which in the eyes of our legal system, is apparently exempt from the 1st Amendment protection that all other art seems to hold.

If rap lyrics are automatically to be taken solely at face value and as completely literal, then the same logic should be applied to all other music, literature and poetry that has been conceived over human history. Metaphors, similes and the concept of figurative language altogether would cease to exist. But that’s ridiculous, right? Art is just that: art, to be interpreted in as many ways as one can imagine. However, rap music is constantly assumed to be devoid of any symbolic, metaphorical or interpretive qualities, or for that matter, the ability to be fictional.

The failure of courts to hold hip-hop in as high regard as other genres of music is insulting and degradative. It denies rap the status of art and encourages nobody to bat an eye at connecting subject matter in lyrics, no matter how fictitious in nature, to a preconceived idea about the defendant’s character. Prosecution can call it “evidence” all that they want; in truth, the use of rap lyrics in court is really an exploitative attempt to assassinate one’s character, violating rappers’ 6th Amendment right to a fair trial in addition to their already disregarded free speech 1st Amendment protections.

This becomes especially apparent when recognizing that hip-hop is the sole genre where its artists become singled out for their creative output, simply by virtue of their art being a part of that genre. The notion of a country music or heavy metal artist appearing in court for an alleged crime, and then being faced with their lyrical content as a means for the prosecution to seek a conviction seems implausible. But for hip-hop, people are becoming dangerously desensitized towards the impulse to do so.

For decades, the American public has built up a deep-seated, preconceived notion around hip-hop, its culture and the artists who make it. A bias doesn’t always have to be conscious, or even intentionally malicious, but the truth is that these internalized stereotypes and fears are still very much alive and incredibly harmful.

To prove this very point, Kubrin cites a study conducted by a social psychologist in her TEDx Talk where two different groups of people were presented with the same set of lyrics. They read: “Well early one evening I was roamin’ around / I was feelin’ kind of mean / I shot a deputy down.” One of the two groups were told that these were rap lyrics, and the other was told that they were lyrics from a country song. Sure enough, despite the lines shown to each group being identical, those who thought that they were reading rap lyrics found them to feel more threatening compared to the other group.

The aforementioned genres of heavy metal and country can be characteristically home to rebellious lyrical topics. Both can also evoke graphic images in people’s minds, but to most, neither scream “criminal.” And yet hip-hop seems to.

We can no longer continue to hold this blatant double standard. Just as the suggestion of using any other art as credible evidence in criminal trials would be no doubt ridiculed, we need to treat hip-hop the same way.

The overt racial undertones to this whole predicament can not be ignored when considering the history and systemic structures that have been ingrained in our society to keep people of color down for hundreds of years. The labels that have been forced upon them to justify this oppression continue to inform and strengthen these subconscious biases held by so many.

Now, the next step is to return the freedom of self expression to these artists who have fought so hard for it. Rappers use their creativity as a means to give themselves a voice and chance at a more equitable socio-economic standing in our country. In response, the legal and judicial systems in America have weaponized the work of rappers against them despite years of the music industry promoting this very aesthetic to be maintained for the sake of marketing and profit. And now those rappers, who at least were able to benefit off of their labor and art, are being punished for it?

It needs to stop.